In January 1989, a group of clinicians (a senior registrar, a clinical research worker, and two behavioural therapists) published a discussion paper in the Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners entitled “Management of chronic (post-viral) fatigue syndrome”. [pdf]

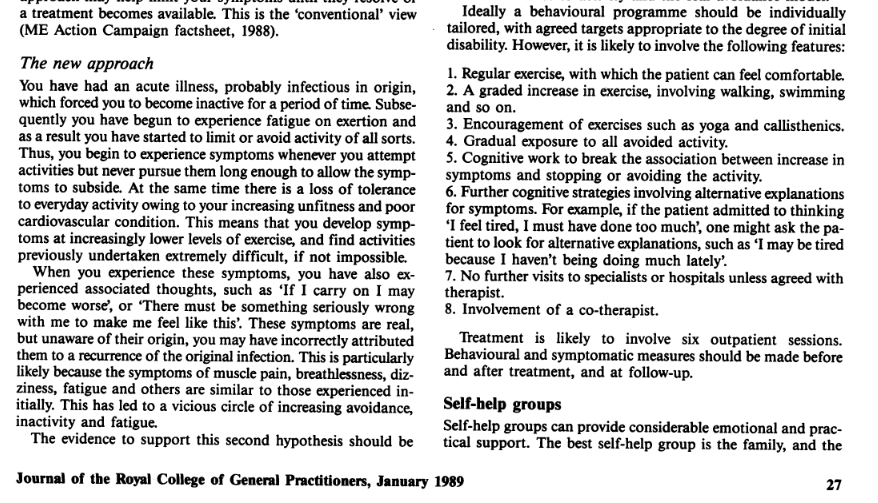

However, they seemed to be writing on the basis of fairly limited information and experience, and much of what they proposed went against what they termed “conventional” advice – advice mainly from charities that had arisen as support groups for patients and clinicians with the condition, such as ME Action Campaign (which later became Action for ME) and the ME Association (formerly the ME Society). They took the view that advice to rest was “nihilistic”, and that patients should be encouraged to engage in regular exercise, particularly “a graded increase in exercise”, in order to overcome their “vicious circle of increasing avoidance, inactivity and fatigue.” They omitted any mention of pacing in their summary of the “conventional” view, so their description was also a gross misrepresentation. The lead author was a Dr Simon Wessely.

As a result, many others wrote in to correct the errors that Wessely and co had made. In a letter a few weeks later, Prof E.J. Field urged that “Wessely and colleagues should evaluate evidence of the nature of the disease… before going overboard on the psychological approach” as it was clear that “the immune system has been shown to be at fault.”

Martin Lev from the ME Action Campaign also wrote in to complain about the paper, pointing out that it ignored the physiological abnormalities in muscle that had been noted in the condition, and that “the authors do not appear to have read the medical literature on ME.”

—–

And then I have to pause slightly, as the process of tracking down the correspondence associated with this paper is frustrated by the lack of adequate linkage through the PubMed record.

Herein lies one of the main problems. Once a paper becomes established in the medical literature, it is often really difficult to uncover the debate that was held about it at the time. We also have no record of how the journals decided which letters to publish, and which ones to discard. In the interests of “balance”, journals will publish a selection of letters that are for and against a particular view, but it won’t show which way the scales were tipped. If feeling was particularly strong on one side, it won’t necessarily be apparent.

I find the process immensely frustrating, because I know that much has been excluded from the record. The fact that it is made harder because even tracking the existing correspondence is hard enough. It’s like chasing multiple threads that have caught on the wind and are flying in all directions at once.

And then, if the authors reply courteously and attempt to address the main points, their reply will seal the discussion, usually without any of the misinformation in the original paper being corrected – it was only a discussion paper after all. But the damage is done. Because only the original paper will be cited, and not the correspondence, or even, as we will see, any subsequent corrective articles. Until the internet and PubMed, that was lost to the dusty academic libraries for those who had the time or the interest to dig it all out again.

—-

As an example of this problem, correspondence about this article (which appeared in the January issue) appeared in both the April and May issues, but the PubMed indexing for the May letters is not complete and misses several important letters.

In the May issue, Rosen et al. noted that Wessely et al. had omitted any mention of hyperventilation and effort syndrome.

Rupert Gude was concerned that not paying attention to the need to rest in the early stages of the disease was likely counterproductive, and although he seemed to have a favourable view towards gradual rehabilitation, was critical of ignoring the variability between patients.

The PubMed record of the contents of this issue then places the remaining letters in the wrong order, which is why they may have been missed from indexing.

The missing letters are below:

P.G. Weaving felt that, although Wessely and colleagues should be admired for their approach “to the management of a difficult group of patients”, they could not “apply their rehabilitative strategies to those people who genuinely suffer from the chronic fatigue syndrome” because of abnormal biochemistry in the muscle of such patients that had been noted.

Nicki Baker wrote as a patient, who had been urged to do so by her GP. She was horrified that Wessely et al. had suggested exercise as a rehab technique. She acknowledges that little had been written in the medical literature about the condition, but pointed out that the authors “appear lamentably unaware that a considerable amount has nonetheless been produced by a number of people with extensive experience of the syndrome and its management, such as the ME Association, [and Drs] Ho-Yen and Wilkinson.”

I don’t know whether it is the case, but I suspect that this may have been what then alerted Darrel Ho-Yen to Wessely’s paper, and prompted him to write his own, as it was published in the January issue of the following year in the British Journal of General Practice. He sought to carefully address the things that Wessely et al had got wrong about the condition and its management. But he was too late. Wessely had got there first. In academic publishing, primacy is king.

This is what Ho-Yen said about Wessely et al.’s approach:

Naturally, Wessely and co responded. They assumed that Ho-Yen only saw “patients with shorter illness durations, referred for a microbiological opinion,” implying that he didn’t really know what he was talking about because he was merely a microbiologist, not realising that Darrel Ho-Yen had at least 7 years clinical experience working with patients with ME before he became a consultant microbiologist at Raigmore Hospital in Inverness. He also had close connection with ME support groups, and with GPs. He had also written a very successful book about patient management of the condition.

In their defensiveness, Wessely et al. show how little they understand about the condition and how to treat it. The thing that strikes me about their reply is how they not only misrepresent what Ho-Yen had said, but also misrepresented the content of their own article.

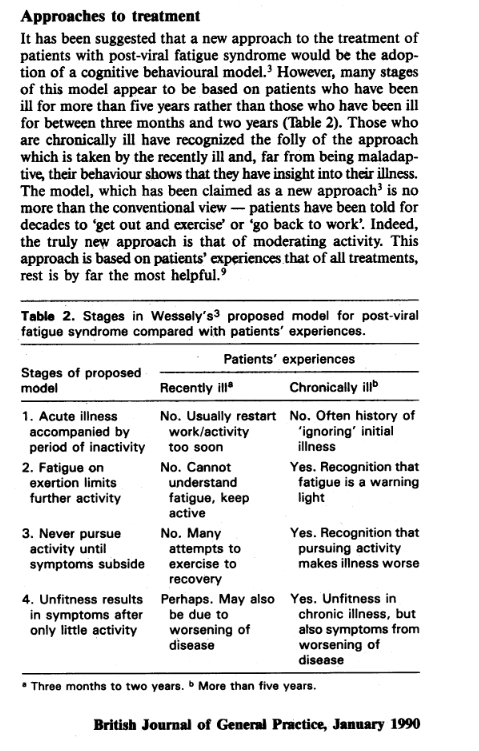

“We disagree… that the management we advocate is to ‘get out and exercise’.” And yet, that is precisely what they were advocating. At least half of the features delineated in their section “Work of treatment” (right-hand column of the extract below) involved exercise as part of the “behavioural programme”.

If what they were actually proposing was more nuanced and carefully controlled than that, they should have made that very clear, if they truly were aware of the damage that exercise could do.

Reading their reply is like watching a crocodile thrashing about in order to muddy the waters. And that is precisely what they ended up doing.

References

Wessely S, David A, Butler S, Chalder T. Management of chronic (post-viral) fatigue syndrome [discussion paper]. J R Coll Gen Pract 1989; 39: 26-29.

Ho-Yen DO. Patient management of post-viral fatigue syndrome. Br J Gen Pract 1990; 40: 37-39.

Leave a comment